Active Record in Rails 4

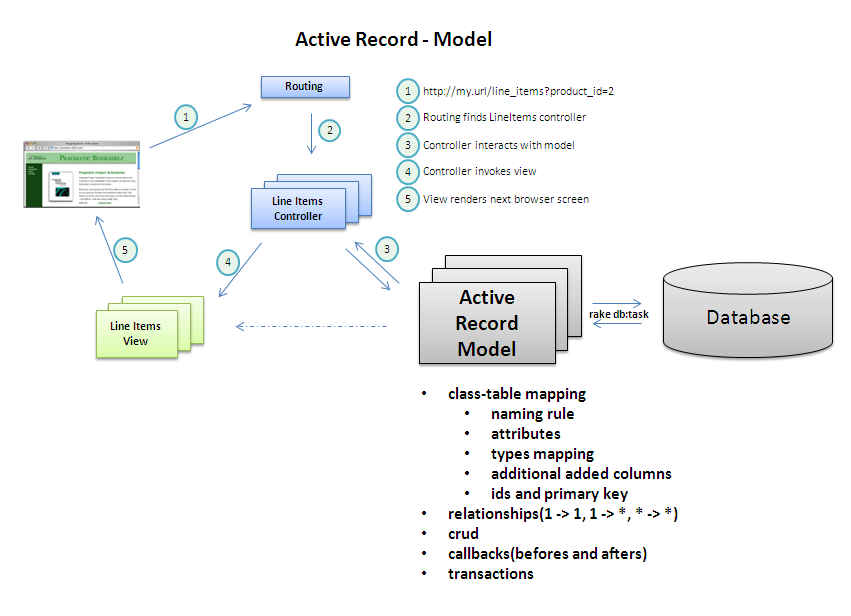

Active Record is the object-relational mapping (ORM) layer supplied with Rails. It is the part of Rails that implements your application’s model.

This will cover:

- class-table mapping(naming rules, model attributes, types mapping, additional added columns, ids and primary keys)

- relationships(one2one, one2many, many2many)

- crud(create, read, update and delete)

- callbacks(befores and afters around crud)

- transactions

Active Record as the Model in MVC:

Defining Your Data

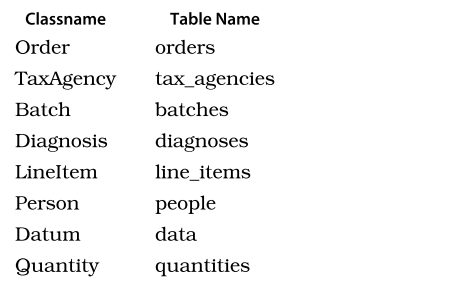

Classname to Table Name

Class names should be singular while the names of tables should be plural.

Although Rails handles most irregular plurals correctly, occasionally you may stumble across one that is not handled correctly. You have two options now:

-

Add new inflection rules in

depot/config/initializers/inflections.rb:ActiveSupport::Inflector.inflections do |inflect| inflect.irregular ‘tax’, ‘taxes’ end

-

Control the table name associated with a given model by setting the table_name for a given class.

class Sheep < ActiveRecord::Base self.table_name = “sheep” end

Attributes

Active Record blurs that distinction(strict boundaries between code and schema), and no other place is that more apparent than in the lack of explicit attribute definitions in the model.

Example:

generator

$ rails generate scaffold Order name address:text email pay_type

migration(in depot/db/migrate/20131105083930_create_orders.rb)

class CreateOrders < ActiveRecord::Migration

def change

create_table :orders do |t|

t.string :name

t.text :address

t.string :email

t.string :pay_type

t.timestamps

end

end

end

model(in depot/app/models/order.rb)

class Order < ActiveRecord::Base

end

db migration(run rake task to apply the migration )

$ rake db:migrate

rails console(list the columns, and play with the model)

$ rails console

Loading development environment (Rails 4.0.1)

>>> Order.column_names

>>> Order.column_names

=> ["id", "name", "address", "email", "pay_type", "created_at", "updated_at"]

>>> order = Order.new

=> #<Order id: nil, name: nil, address: nil, email: nil, pay_type: nil, created_at: nil, updated_at: nil>

2.0.0-p247 :004 > order.name = 'just a test'

=> "just a test"

2.0.0-p247 :005 > order.save

(0.2ms) begin transaction

SQL (48.0ms) INSERT INTO "orders" ("created_at", "name", "updated_at") VALUES (?, ?, ?) [["created_at", Tue, 26 Nov 2013 08:18:23 UTC +00:00], ["name", "just a test"], ["updated_at", Tue, 26 Nov 2013 08:18:23 UTC +00:00]]

(7.5ms) commit transaction

=> true

Continue reading: Migrations in Rails 4.

Where Are Our Attributes?

The notion of a database administrator (DBA) as a separate role from programmer has led some developers to see strict boundaries between code and schema. Active Record blurs that distinction, and no other place is that more apparent than in the lack of explicit attribute definitions in the model.

But fear not. Practice has shown that it makes little difference whether we’re looking at a database schema, a separate XML mapping file, or inline attributes in the model. The composite view is similar to the separations already happening in the Model- View-Control pattern—just on a smaller scale.

Once the discomfort of treating the table schema as part of the model definition has dissipated, you’ll start to realize the benefits of keeping DRY. When you need to add an attribute to the model, you simply have to create a new migration and reload the application.

Taking the “build” step out of schema evolution makes it just as agile as the rest of the code. It becomes much easier to start with a small schema and extend and change it as needed.

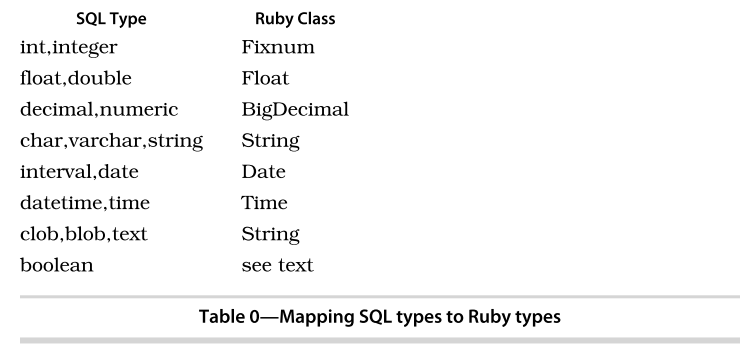

SQL Types & Ruby Types

Additional Columns

A number of column names have special significance to Active Record. Here’s a summary:

- created_at, created_on, updated_at, updated_on: automatically updated with the timestamp of a row’s creation or last update, the _on suffix for date columns and the _at suffix for columns that include a time.

- id: the default name of a table’s primary key column.

- xxx_id: the default name of a foreign key reference to a table named with the plural form of xxx.

- xxx_count: a counter cache for the child table xxx.

Additional plugins, such as acts_as_list, may define additional columns.

Locating and Traversing Records

Both primary keys and foreign keys play a vital role in database operations. Here’s a summary:

- go with the flow and let it add the

idprimary key column to all your tables - override the default name of the primary key for a table by specifying

self.primary_key = "isbn"in Active Record model. - as far as Active Record is concerned, the primary key attribute is always set using an attribute called id.

- if we override the primary key column’s name, we also take on the responsibility of setting the primary key to a unique value before we save a new row.

- Rails considers two model objects as equal (using ==) if they are instances of the same class and have the same primary key.

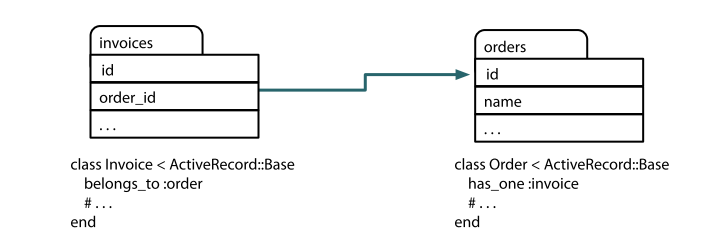

Specifying Relationships in Models

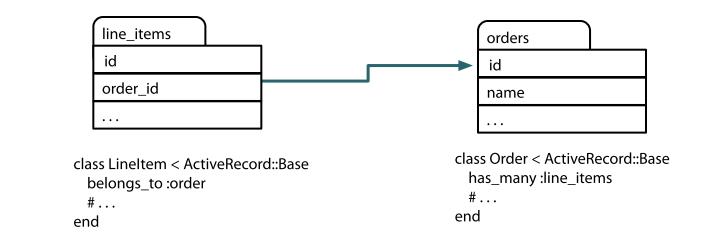

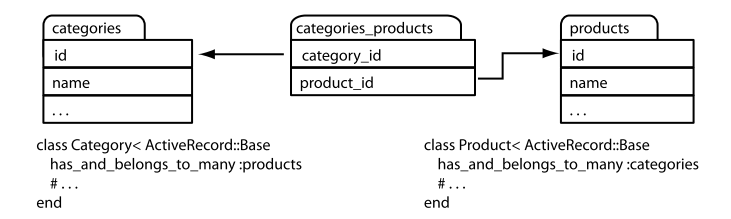

Active Record supports three types of relationship between tables: one-to-one, one-to-many, and many-to-many. You indicate these relationships by adding declarations to your models: has_one, has_many, belongs_to, and the wonderfully named has_and_belongs_to_many.

One-to-One Relationships

One-to-Many Relationships

Many-to-Man Relationships

CRUD(Create, Read, Update, Delete)

Read(new and create)

The new() constructor creates a new Order object in memory; we have to remember to save it to the database at some point. Active Record has a convenience method, create(), that both instantiates the model object and stores it into the database.

save, save!, create, and create! The variants differ in the way they report errors:

savereturns true if the record was saved; it returns nil otherwise.save!returns true if the save succeeded; it raises an exception otherwise.createreturns the Active Record object regardless of whether it was successfully saved. You’ll need to check the object for validation errors if you want to determine whether the data was written.create!returns the Active Record object on success; it raises an exception otherwise.

Read(find, where, order, limit, offset, select, joins, readonly, group, lock, statistics, scopes, native sql)

Update(save)

If you have an Active Record object (perhaps representing a row from our orders table), you can write it to the database by calling its save() method. If this object had previously been read from the database, this save will update the existing row; otherwise, the save will insert a new row.

Delete(delete, delete_all, destroy, destroy_all)

delete() takes a single id or an array of ids and deletes the corresponding row(s) in the underlying table, while delete_all() * delete rows matching a given condition (or all rows if no condition is specified).

- operate at the database level

- return values are typically the number of rows affected.

- an exception is not thrown if the row doesn’t exist prior to the call.

destroy() instance method deletes from the database the row corresponding to a particular model object. It then freezes the contents of that object, preventing future changes to the attributes.

destroy() (which takes an id or an array of ids) and destroy_all() (which takes a condition). Both methods read the corresponding rows in the database table into model objects and call the instance-level destroy() method of those objects. Neither method returns any- thing meaningful.

Why do we need both the delete and destroy class methods? The delete methods bypass the various Active Record callback and validation functions, while the destroy methods ensure that they are all invoked. In general, it is better to use the destroy methods if you want to ensure that your database is consistent according to the business rules defined in your model classes.

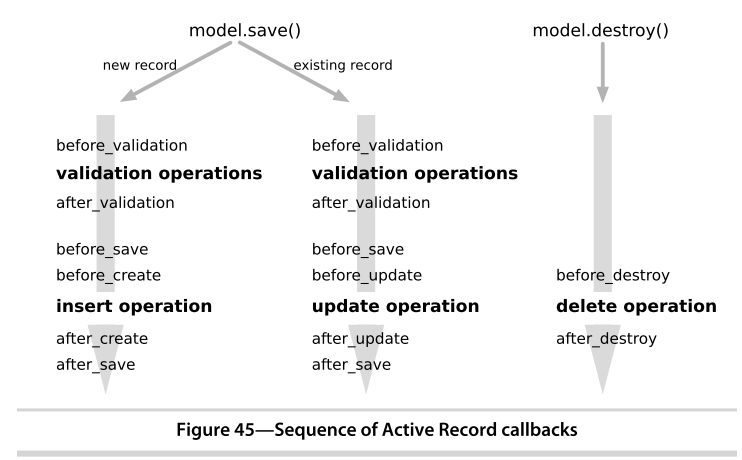

Participating in the Monitoring Process(Callback)

Active Record controls the life cycle of model objects—it creates them, monitors them as they are modified, saves and updates them, and watches sadly as they are destroyed. Using callbacks, Active Record lets our code participate in this monitoring process. We can write code that gets invoked at any significant event in the life of an object. With these callbacks we can perform complex validation, map column values as they pass in and out of the database, and even prevent certain operations from completing.

Active Record defines sixteen callbacks. Fourteen of these form before/after pairs and bracket some operation on an Active Record object.

Rails wraps the sixteen paired callbacks around the basic create, update, and destroy operations on model objects.

Additional summary:

- Perhaps surprisingly, the

beforeandaftervalidation calls are not strictly nested. - The

before_validationandafter_validationcalls also accept theon: :createoron: :updateparameter, which will cause the callback to only be called on the selected operation. - In addition to these sixteen calls, the

after_findcallback is invoked after any find operation, andafter_initializeis invoked after an Active Record model object is created.

Grouping Related Callbacks Together. To have your code execute during a callback, you need to write a handler and associate it with the appropriate callback. There are two basic ways of implementing callbacks:

- To define a callback is to declare handlers. A handler can be either a method or a block. You associate a handler with a particular event using class methods named after the event. To associate a method, declare it as private or protected, and specify its name as a symbol to the handler declaration. To specify a block, simply add it after the declaration. This block receives the model object as a parameter.

- To define the callback instance methods using callback objects, inline methods (using a proc), or inline eval methods (using a string).

If you have a group of related callbacks, it may be convenient to group them into a separate handler class. These handlers can be shared between multiple models. A handler class is simply a class that defines callback methods (before_save(), after_create(), and so on). Create the source files for these handler classes in app/models.

Transactions

Transactions are actually very subtle. They exhibit the so-called ACID properties: they’re Atomic, they ensure Consistency, they work in Isolation, and their effects are Durable (they are made permanent when the transaction is committed). It’s worth finding a good database book and reading up on transactions if you plan to take a database application live.

A database transaction groups a series of changes together in such a way that either the database applies all of the changes or it applies none of the changes.

Transactions to the rescue. A transaction is something like the Three Muske-teers with their motto “All for one and one for all.” Within the scope of a transaction, either every SQL statement succeeds or they all have no effect. Putting that another way, if any statement fails, the entire transaction has no effect on the database.

Active Record uses transaction() method to execute a block in the context of a particular database transaction:

Account.transaction do

account1.deposit(100)

account2.withdraw(100)

end

Active Record wasn’t keeping track of the before and after states of the various objects—in fact it couldn’t, because it had no easy way of knowing just which models were involved in the transactions.

Active Record is smart enough to wrap all the updates and inserts related to a particular save() (and also the deletes related to a destroy()) in a transaction; either they all succeed or no data is written permanently to the database. You need explicit transactions only when you manage multiple SQL statements yourself.

Reference

blog comments powered by Disqus