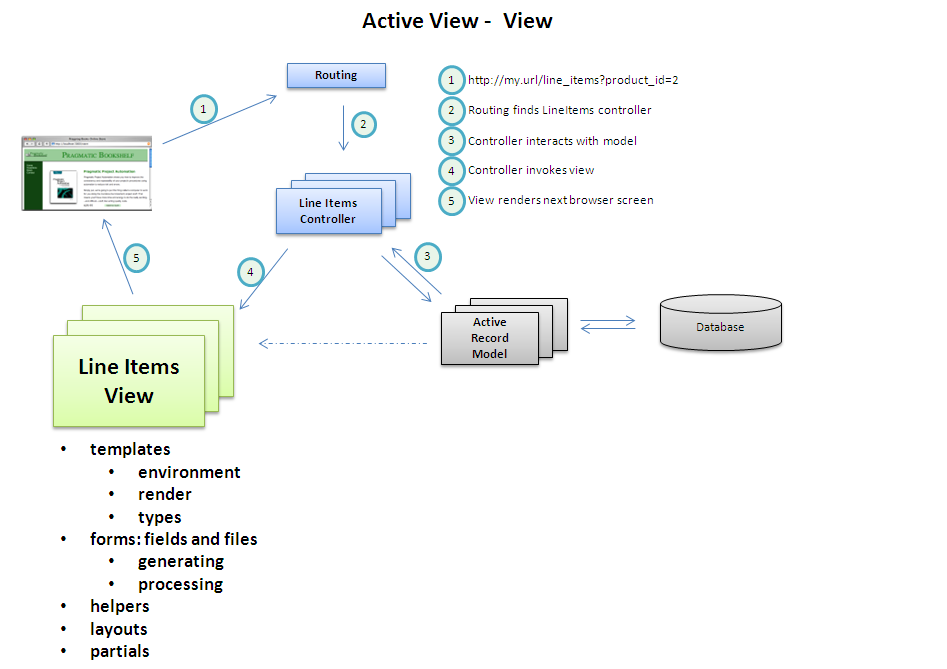

Action View in Rails 4

Action View encapsulates all the functionality needed to render templates, most commonly generating HTML, XML, or JavaScript back to the user.

Action View as the View in MVC:

Templates

When you write a view, you’re writing a template: something that will get expanded to generate the final result.

Where Templates Go

The render() method expects to find templates in the app/views directory of the current application.

Each directory typically contains templates named after the actions in the corresponding controller. You can also have templates that aren’t named after actions. You render such templates from the controller using calls such as these:

render(action: 'fake_action_name')

render(template: 'controller/name')

render(file: 'dir/template')

The Template Environment

Templates contain a mixture of fixed text and code. The code in the template adds dynamic content to the response. That code runs in an environment that gives it access to the information set up by the controller:

- all instance variables of the controller.

- the controller object’s flash, headers, logger, params, request, response and session.

- the current controller object(using the attribute named

controller). - the path the the base directory of the templates is stored in the attribute

base_path.

What Goes in a Template

Out of the box, Rails supports four types of templates:

- Builder tempates use the Builder library to construct XML responses.

- CoffeeScript tempates create JavaScript.

- ERb templates mixing content and embedded Ruby to generate HTML pages typically.

- SCSS tempates create CSS stylesheet.

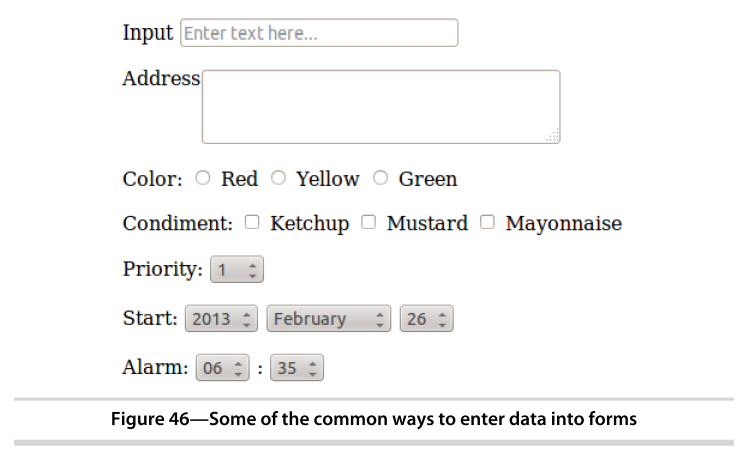

Generating Forms

HTML provides a number of elements, attributes, and attribute values that control how input is gathered. You certainly could hand-code your form directly into the template, but there really is no need to do that. Rails provides a number of helpers that assist with this process.

Code to produce that form:

<%= form_for(:model) do |form| %>

<p>

<%= form.label :input %>

<%= form.text_field :input, :placeholder => 'Enter text here...' %>

</p>

<p>

<%= form.label :address, :style => 'float: left' %>

<%= form.text_area :address, :rows => 3, :cols => 40 %>

</p>

<p>

<%= form.label :color %>:

<%= form.radio_button :color, 'red' %>

<%= form.label :red %>

<%= form.radio_button :color, 'yellow' %>

<%= form.label :yellow %>

<%= form.radio_button :color, 'green' %>

<%= form.label :green %>

</p>

<p>

<%= form.label 'condiment' %>:

<%= form.check_box :ketchup %>

<%= form.label :ketchup %>

<%= form.check_box :mustard %>

<%= form.label :mustard %>

<%= form.check_box :mayonnaise %>

<%= form.label :mayonnaise %>

</p>

<p>

<%= form.label :priority %>:

<%= form.select :priority, (1..10) %>

</p>

<p>

<%= form.label :start %>:

<%= form.date_select :start %>

</p>

<p>

<%= form.label :alarm %>:

<%= form.time_select :alarm %>

</p>

<% end %>

Not shown in this example are hidden_field() and password_field(). A hidden field is not displayed at all, but the value is passed back to the server. This may be useful as an alternative to storing transient data in sessions, enabling data from one request to be passed onto the next. Password fields are displayed, but the text entered in them is obscured.

This is more than an adequate starter set for most needs. Should you find that you have additional needs, you are quite likely to find a helper or gem is already available for you. A good place to start is with the Rails Guides.

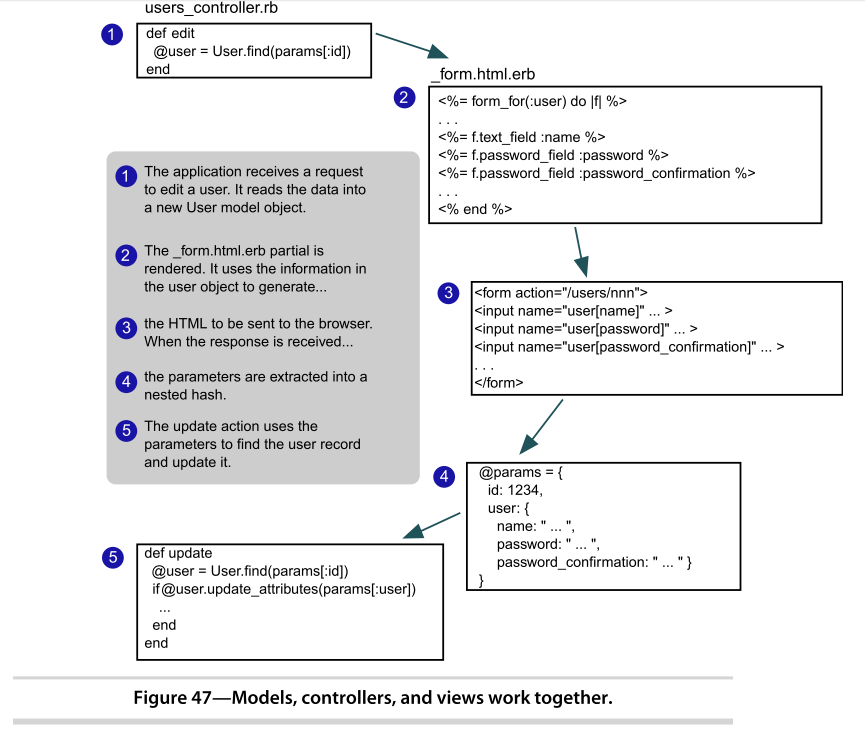

Processing Forms

Uploading Files

In HTTP, files are uploaded as a multipart/form-data POST message. As the name suggests, forms are used to generate this type of message. Within that form, you’ll use one or more <input> tags with type="file". When rendered by a browser, this tag allows the user to select a file by name. When the form is subsequently submitted, the file or files will be sent back along with the rest of the form data.

If you’d like an easier way of dealing with uploading and storing images, take a look at thoughtbot’s Paperclip or Rick Olson’s attachment_fu plugins.

Using Helpers

It’s perfectly acceptable to put some code in templates—that’s what makes them dynamic. However, it’s poor style to put too much code in templates. There are three main reasons for this:

- the more code you put in the view side of your application, the easier it is to let discipline slip and start adding application-level functionality to the template code. This is definitely poor form and will pay off when you add new ways of viewing the application.

html.erbis basically HTML, putting a bunch of Ruby code in there just makes it hard to work with.- code embedded in views is hard to test, whereas code split out into helper modules can be isolated and tested as individual units.

Rails provides a nice compromise in the form of helpers. A helper is simply a module containing methods that assist a view. Helper methods are output- centric. They exist to generate HTML (or XML, or JavaScript)—a helper extends the behavior of a template.

Additional summary:

- By default, each controller gets its own helper module.

- Additionally, there is an application-wide helper named

application_helper.rb. - Rails comes with a bunch of built-in helper methods, available to all views for formatting and linking.

- the

JavaScriptHelpermodule defines a number of helpers for working with JavaScript. - By default, image and stylesheet assets are assumed to live in the images and stylesheets directories relative to the application’s assets directory

Reducing Maintenance with Layouts and Partials

One of the driving ideas behind Rails is honoring the DRY principle and eliminating the need for duplication.

The average website, though, has lots of duplication:

• Many pages share the same tops, tails, and sidebars. • Multiple pages may contain the same snippets of rendered HTML (a blog site, for example, may display an article in multiple places). • The same functionality may appear in multiple places. Many sites have a standard search component, or a polling component, that appears in most of the sites’ sidebars.

Rails provides both layouts and partials that reduce the need for duplication in these three situations.

Layouts

Layouts: Rails allows you to render pages that are nested inside other rendered pages.

- layouts set out a standard HTML page, with the head and body sections.

- Inside the layout template, calling

yieldretrieves its content. - layouts are controller-specific.

- Rails will by default look for a layout called

storewhen the current request is being handled by a controller calledstore. - You can override this using the

layoutdeclaration inside a controller. - You can qualify which actions will have the layout applied to them using the

:onlyand:exceptqualifiers.

- Rails will by default look for a layout called

- If you create a layout called application in the

layoutsdirectory, it will be applied to all controllers that don’t otherwise have a layout defined for them. - Specifying a layout of nil turns off layouts for a controller.

- Rails supports changing the appearance of a set of pages at runtime with dynamic layouts.

- Subclasses of a controller use the parent’s layout unless they override it using the

layoutdirective. - Individual actions can choose to render using a specific layout (or with no layout at all) by passing

render()the:layoutoption. - Layouts have access to all the same data that’s available to conventional templates.

- In addition, any instance variables set in the normal template will be available in the layout.

Partials

You can think of a partial as a kind of subroutine. You invoke it one or more times from within another template, potentially passing it objects to render as parameters. When the partial template finishes rendering, it returns control to the calling template.

- Internally, a partial template looks like any other template.

- Externally, the name of the file containing the template code must start with an underscore character, differentiating the source of partial templates from their more complete brothers and sisters.

-

Other templates use the render(partial:) method to invoke paritals, like:

render(partial: ‘article’, object: @an_article, locals: { authorized_by: session[:user_name], from_ip: request.remote_ip })

Additional summary:

- partials and collections. Using

renderwith:collectionand:spacer_templateparameters to work in conjunction with the partials. - shared templates. This makes it easy to share partials and subtemplates across controllers.

- partials with layouts. Partials can be rendered with a layout, and you can apply a layout to a block within any template.

- partials and controllers. Partials give controllers the ability to generate fragments from a page using the same partial template as the view itself.

Taken together, partials and layouts provide an effective way to make sure that the user interface portion of your application is maintainable. But being maintainable is only part of the story; doing so in a way that also performs well is also crucial.

Reference

blog comments powered by Disqus